How to feel about the metacrisis

Here is one way to understand the metacrisis: through our evolutionary developments of cognition and technology, super-charged by hydrocarbons, humanity has entered an epoch of exponential growth. Over the past century, we have reached a scale that is breaching planetary boundaries while concentrating power in the hands of narcissistic sociopaths, and locking us into collective dynamics of extraction and competition. On this trajectory, our civilization will collapse and perish. The metacrisis is the self-terminating process that is unfolding globally today.

In prior articles, I considered the role of masculinity, as well as how to think about the metacrisis. This is a topic that continues to be very rich for me, personally. Today, I’m going to share my perspectives on how to feel about the metacrisis: the emotional, psychological, and somatic ties to the cognitive awareness of the emergent turmoil.

For starters, I want to recommend this powerful conversation between John Vervaeke, Iain McGilchrist, and Daniel Schmachtenberger, titled “The Psychological Drivers of the Metacrisis.” In case you don’t have three and a half hours to watch the video, some of the points that stand out to me from their discussion are:

In the history of humanity, the civilizations that prioritized power, technology, and production conquered the civilizations that prioritized peace, balance, and reciprocity. These drivers have led to our current situation of hyper-competition and extraction, which is ultimately self-terminating. As long as the group that prioritizes the pursuit of power is the group that wins, we are going to continue down this path.

Our political and economic hierarchies are set up in a way that people who care about power and are good at manipulating power end up at the top: narcissistic sociopaths. While people with these traits represent a small fraction of humans, they hold an overwhelming concentration of power which determines the conditions and directions of humanity.

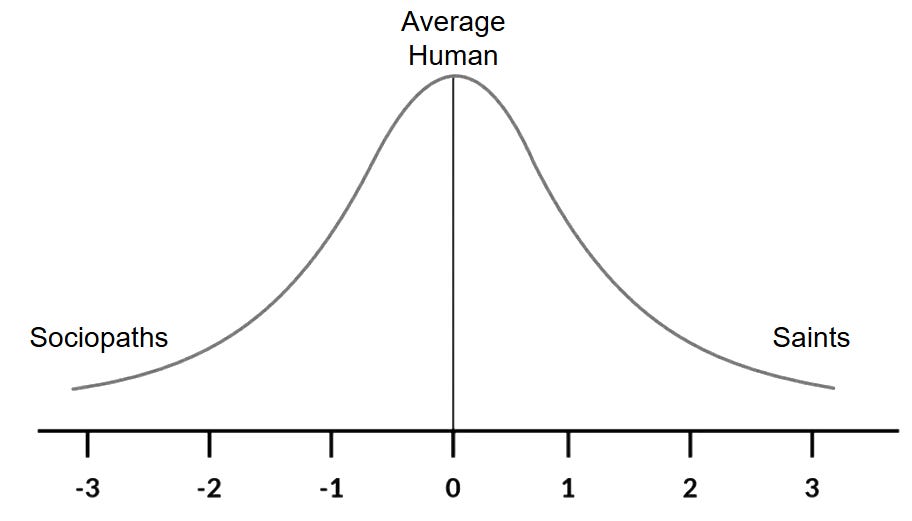

I like illustrations, so let’s make a diagram of this one. If we imagine plotting the moral orientations of humans, we would likely see a gaussian distribution where most humans have an average amount of kindness and wickedness and then there is one tail of increasingly moral folks and another tail of increasingly cruel folks. That graph would look like this:Figure 1. Gaussian distribution of the morality of human population

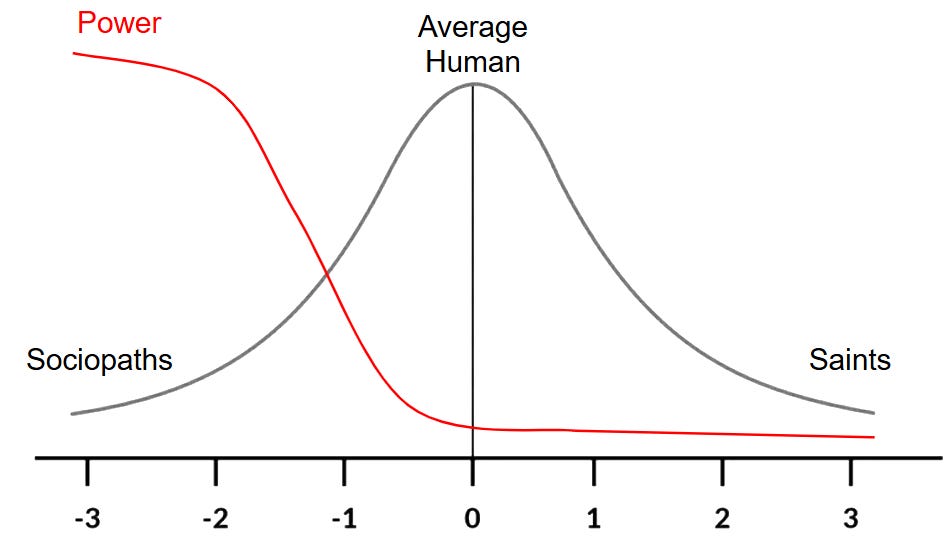

Schmachtenberger makes the very astute point that the amount of power wielded by humans follows a power curve, where the sociopaths hold exponentially more power than the rest of the population. That graph looks like this:

Figure 2. Distribution of power and distribution of moral development

The point of this graph is to illustrate that a small fraction of our population holds the vast majority of resources and influence collectively. That fraction is the subset that we would least want to be designing civilization.

With the Western Enlightenment and the industrial revolution, the rational left-brain has become the dominant psychological trait, over the relational, feeling-oriented right-brain. The hyper-rationalization of humans has created a whole slew of problems, notably, a dissociation from the sacredness of life.

These observations brilliantly illuminate some of the reasons we arrived in the situation we find ourselves in today. They lead to some very important questions like, “If power-driven societies win politically and economically over wisdom-centered ones, is it possible to create a power-literate wisdom-centered society?”1 and “How can the next generation of religion re-introduce the sacred into a materialistic society?”

There are two additions that I would offer to the “Psychological Drivers” conversation: one I will touch on briefly, and the second will be the primary focus for today’s article.

Here’s the brief comment: Both social power and the experience of the sacred can and should be examined through a developmental lens. Individuals and societies develop through a series of discrete stages (or paradigms). For a full discussion of these stages, see my article, The Developmental Paradigms of Consciousness. Each stage will have its own orientation to power and its own relationship with the sacred. Importantly, the higher an individual or culture advances, the more they orient to empowerment (versus holding power over others), and the more they experience the sacred (as opposed to a material or mundane world). Therefore, to the question of how we create a power-literate wisdom-centered society, my answer is that we support healthy expressions of each developmental stage and we create conveyor-belts for the advancement into the higher stages like integral.2 The reframe this perspective provides is that our political and corporate leaders are not, by and large, the most successful people, but rather are pathological products of an early developmental society. The answer is to offer resources for these folks to grow and mature, and to evolve the systems that produce and exalt them. For deeper dives, I discuss the trajectory of how we experience the sacred in The Organic Masculine,3 and the progression of social power in Primal Drives.4

My second observation is that, while the “Psychological Drivers” discussion beautifully articulates the need to shift from rational to relational intelligence, the conversation itself remains very heady. It’s an intellectual examination of the metacrisis pickle. I hold each of these gentlemen in very high regard, but despite brilliantly taxonomizing said pickle, they did not actually come into their bodies to taste the pickle. My goal with this article is to get into the right hemisphere and feel some things!

Figure 3. A spicy metacrisis pickle

Disconnection and the Metacrisis

Have you ever noticed how challenging it is to feel the crisis on an emotional level? For me, it takes effort to open up my emotions on this topic. And then, once I do, I have a hard time staying in them. I shift back to intellectualization on the topic, or I move onto something else entirely.

Let’s give it a shot right now by asking the question: What do you love about nature? Sit with this for a few moments. For me, it’s a resource and a sanctuary. It’s where I go to connect with my wildness. I feel most myself in nature. Maybe you find it beautiful or majestic. Maybe there are certain animals or places that you feel deeply connected with. Now, drop beneath your discursive thinking and feel your love and your care. I can feel my heart open and this core recognition that my aliveness is the same aliveness as nature - there’s a sense of communion that I feel throughout my whole body. That’s me. Whatever it is for you, welcome it.

Now, step two: know that everything you love about nature will most likely no longer exist three generations from now. When our great-grandchildren are our age, our best guesses tell us that the things we love most about nature will be gone or radically reduced. Let yourself sink into this. It’s such a downer, right? Like, unbelievably horrifying, sad, infuriating, and depressing. And it’s intense! To really be with the immensity of our sane emotional response to this destruction is no small task.

And so, speaking for myself, predictably, I back off and move on with my life. I might come back around in a week or a month. But I don’t stay in this emotional quagmire. I disconnect.

In my perspective, the fundamental somatic sense that we hold toward the metacrisis is disconnection. It’s too big, too intense, and too painful, so we disconnect.

What if, the psychological disconnection that we experience is not solely a reaction to the metacrisis? Can we agree that disconnection from the natural world is a core cause of the metacrisis? Anyone who is really emotionally connected would not be able to burn down a rainforest or dump plastic into the ocean. And yet, the lifestyle that we are living today contributes to these horrors along with a whole host of other impacts. It is because we are disconnected that this is able to continue to happen.

Now let’s take an even wider lens: What if disconnection is even more than a cause of and a reaction to the metacrisis? In my view, disconnection is the psychological component of the metacrisis itself. There is one massive meta-phenomenon which encompasses both our interior psycho-somatic dissociation and our exterior destructive actions. We cannot have one without the other. The deterioration of the external world is both a cause and result of our internal disconnection—they are so deeply causally entangled, that it make sense to view them as one meta-phenomena: the metacrisis.

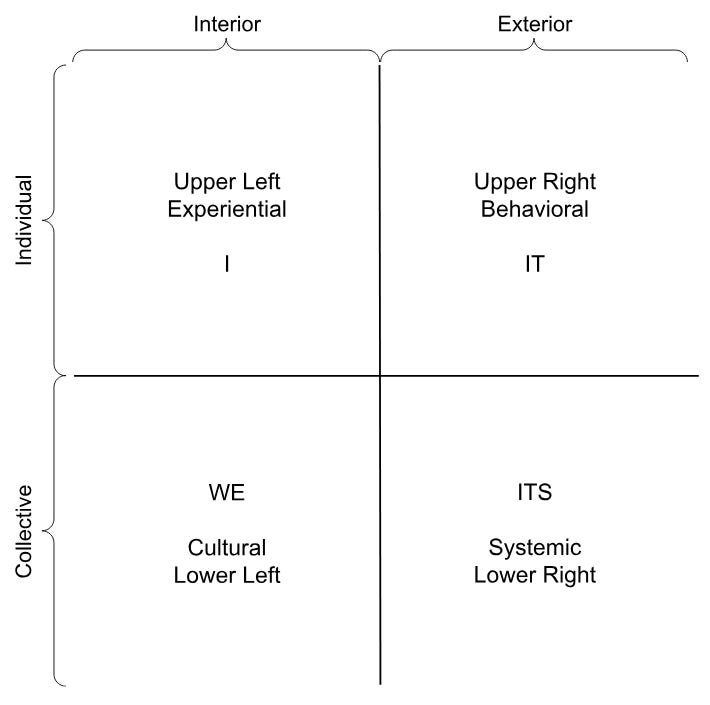

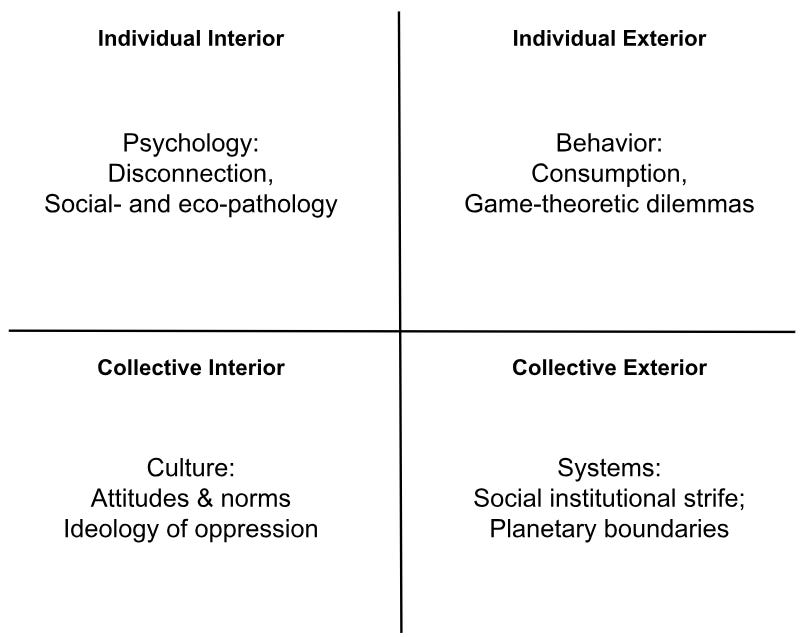

It’s not obvious to view psychological disconnection and ecosystem collapse as a single entity. I arrived at this conclusion by using integral theory’s four-quadrant map, which claims that every entity has four dimensions of being-in-the-world: Individual interior (1st-person “I”); individual exterior (3rd-person “it”); collective exterior (3rd-person “its”); and collective interior (2nd-person “we”). (Check out my article, A Friendly Primer on Integral Theory for a full discussion of this framework).

Figure 4. The four quadrant model.5

The brilliance embedded in the term metacrisis is that it asks us to take a step back from examining individual crises and instead to see the entanglement of multiple systems in crisis as a single entity: a metacrisis. Or, in lay terms: a clusterfuck.

From the perspective of integral theory, every entity occupies these four quadrants. Each individual thing simultaneously holds (1) interior prehension, (2) exterior form, (3) membership in a population, and (4) membership in a culture. In integral parlance, entities tetra-enact. It’s beyond the scope of this article to get into why or how I believe this to be an accurate description of reality, but I’ll leave a few breadcrumbs in these footnotes to say my position6 mirrors that of Ken Wilber.7

So now that we’ve established that there is an entity we can point to called the metacrisis, and argued that every entity has four dimensions of being-in-the-world, the next question is, how does the entity of the metacrisis enact across these four quadrants?

Figure 5. The four quadrants of the metacrisis.

Briefly put, the metacrisis shows up (1) in our individual psychological experiences of disconnection and pathology, (2) in our individual behaviors toward consumption and the game-theory dilemmas (like the prisoner’s dilemma and the tragedy of the commons) that contribute to the crisis, (3) in our economy, geo-politics, and environmental impacts, and (4) our cultural divisiveness.

In my article, Masculinity and the Polycrisis, I pointed out that most discussions of the metacrisis focus solely on the lower right quadrant of our social and environmental systems. I went on to link our cultural crisis of masculinity with the systemic crises in the external world. Now, in this article, my goal is to further include the psychological and emotional aspects of the upper left quadrant. This is a radically more holistic perspective on the metacrisis and therefore a (hopefully) more powerful and useful tool.

We feel that the AQAL framework provides a powerful analysis of the many currents involved in creating, perpetuating, and responding to our historical and contemporaneous environmental crises. Integral Ecology highlights that any anthropogenic ecological crisis is the result of a complex tetra-mesh of the 4 terrains and their various levels of complexities. Thus, any crisis is the result of a complex and unique mixture of fractured consciousness, unsustainable behaviors, dysfunctional cultures, and broken systems. To identify only one or a couple of these contributing factors and hold them up as the main culprit will not help anyone to effectively address these crises.

—Esbjorn-Hargens and Zimmerman8

My goal at this point, is that we’re all on-board with the idea that disconnection is not merely a symptom, but is itself a core component of the metacrisis. Now I’d like to take a deeper look at how this disconnection manifests in our psyches.

The Web of Disconnection

[Note: this section is adapted from my book, Primal Drives, and much of it is presented verbatim.]

At the individual interior level, I am both a cause of the metacrisis and suffer harm as a result. The core internal experience is disconnection. My modern lifestyle has insulated me from the rhythms of nature. This process of disconnection has been developing through successive generations over the last ten thousand years. I am disconnected from the beauty and abundance of nature. At the same time, I’m disconnected from the places where harm is being caused: I’m not exposed to the strip mines or deforestation or pacific trash gyres. In addition, the impacts on nature are happening slow enough that it’s challenging to recognize. Each year, the fish are a little smaller and fewer, and the forests are a little drier. On a geological timescale, this change is happening incredibly quickly, but on a human timescale it’s almost invisible. All of these factors contribute to my disconnection from the natural world. For most of our history, humans were not only immersed in nature, we were nature. Today, “nature” is a place I go to visit for recreation.

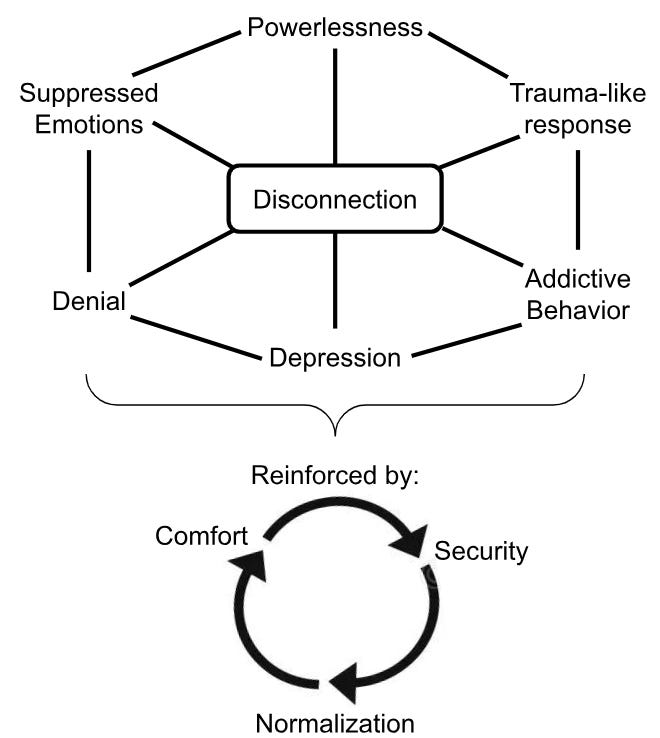

My psychological disconnection from nature then causes a whole host of other distortions and coping mechanisms, illustrated below.

Figure 6. Web of disconnection and cycle of continuation

My psychological disconnection from both the gifts of nature and the harm that I am participating in contributes to powerlessness, suppressed emotions, trauma-like responses, addictive behavior, denial, and acceptance of the status quo. This forms a web of maladaptive pathology that I get stuck in. The web of disconnection is reinforced by my comfort, perceived security, and the normalization that this is the way things are. My ego’s first priority in selecting between options will be to choose what is familiar. These three factors, comfort, security, and normalization, keep me participating in the processes contributing to the metacrisis, even when I’m able to recognize it’s not in my best interest. Let’s consider each aspect in the web of disconnection.

Powerlessness occurs as I internalize these self-terminating human processes. I view the problems as so large and pervasive that there is literally nothing I can do to make a positive impact. In addition, I give precedence to securing my individual needs before working toward the collective good: “I would do more for the environment, but I need to work just to make ends meet.” This powerlessness creates a belief that large-scale transformation is impossible, which becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. I then collude with the broken system.

Powerlessness could be defined as that which prevents us from realizing the fullness of both our power-from-within (the creative potential that serves as the basic foundation for our renewed vision) and our power-with (our ability to act in concert with others).

—Hathaway and Boff9

The next node on the web is suppressed emotions. In the face of ecological violence, I will suppress both my challenging emotions like pain, grief, fear, and anger, as well as the more pleasurable ones like joy and awe. I see the state of what’s happening to the planet and my natural response would be to feel. The natural world is undergoing a mass death event. The pain that I feel is a sign of my connection with the suffering of the world. However, I habitually suppress these emotions, manage my state, and distract myself. The more I cut myself off from feeling, the more of my lifeforce I disconnect from. By suppressing the challenging emotions, I also limit my capacity to feel the positive emotions. It is natural to grieve for the earth, to be angry about what’s happening, to fear for future generations, and to feel the pain of ecological collapse. But it is equally important to enjoy the earth, to love her passionately, and to celebrate nature. Moreover, making space for these feelings is necessary in order to heal and to step out of the web of disconnection.

What we are dealing with here is akin to the original meaning of compassion: “suffering with.” It is the distress we feel on behalf of the larger whole of which we are a part… That pain is the price of consciousness in a threatened and suffering world. It is not only natural; it is an absolutely necessary component of our collective healing.

—Macy and Brown10

The next node covers trauma-like responses. As a somatic therapist, I recognize a few different types of trauma. An acute trauma is a single shocking event where a person’s nervous system moves outside the window of tolerance and the excess emotional energy becomes stuck in the body. Chronic trauma, on the other hand, develops through repeated exposure to a harmful stimulus or environment. Over time, chronic trauma negatively impacts a whole host of developmental processes including “emotion regulation, impulse control, attention and cognition, dissociation, interpersonal relationships, and self and relational schemas.”11 My disconnection from the natural world functions like chronic trauma. Connection with nature, plants, animals, rivers, oceans, forests, and ecosystems are regulating and relational. Without these stimuli and relationships, I become increasingly prone to the same numbing out and immobilization that is characteristic of chronic trauma.

Understanding my disconnection from nature as a trauma-like response also illuminates why I feel a draw toward the next node, addictive behavior. Addiction is a coping mechanism to avoid pain.12 In addition to the more commonly understood forms of addiction like drug use or pornography, the eco-pathology of addiction includes consumption, workaholism, and social media. These are all forms of distraction which keep me from feeling the pain of the metacrisis and simultaneously further disconnect me from the natural world.13

Technological society’s dislocation from the only home we have ever known is a traumatic event that has occurred over generations, and that occurs again in each of our childhoods and in our daily lives. In the face of such a breach, symptoms of traumatic stress are no longer the rare event caused by a freak accident or battering weather, but the stuff of every [person]’s daily life. As human life comes to be structured increasingly by mechanistic means, the psyche restructures itself to survive. The technological construct erodes primary sources of satisfaction once found routinely in life in the wilds, such as physical nourishment, vital community, fresh food, continuity between work and meaning, unhindered participation in life experiences, personal choices, community decisions, and spiritual connection with the natural world. These are the needs we were born to have satisfied. In the absence of these we will not be healthy. In their absence, bereft and in shock, the psyche finds some temporary satisfaction in pursuing secondary sources like drugs, violence, sex, material possessions, and machines. While these stimulants may satisfy in the moment, they can never truly fulfill primary needs. And so the addictive process is born.

—Chellis Glendinning14

The next aspect of the web of disconnection is denial. At the extreme end, this manifests as outright negation of the scientific community’s consensus about humanity’s harmful impacts. On a more subtle level, I find myself holding a cognitive dissonance about this crisis. It’s too much to be present to. So I focus on other things and push my awareness of the metacrisis into the background. Again, this has two effects: It allows me to continue to participate in, and benefit from, our exploitation of ecosystems, and it further isolates me from the natural world, which embeds me deeper into the web of disconnection.

The same psychological defenses, distortions, and inauthenticies that contribute to global crises may also result from them. For as stresses mount, so also does the temptation to resort to defensiveness and inauthenticity. Yet denial, repression, or other defenses are always purchased at the cost of our full potential and humanity. When we distort our image of the world we distort our image of ourselves. When we fear to look out at the world we fear to look into ourselves. Therefore we remain unaware of the powers of potential that lie within us and are us; the powers of potential that are the major resources we have to offer to the world.

–Roger Walsh15

Although this model is by no means exhaustive, the final node on my web of disconnection is depression. Today, the World Health Organization ranks depression as the single largest contributor to disability.16 Depression is a complex mental health process that frequently interconnects with powerlessness, suppressed emotions, trauma, addictive behaviors, and denial—every other node in the web of disconnection. Depression often goes hand in hand with anxiety, and for me, the core experience is one of despair. It is a case, not just of powerlessness, but of hopelessness to address the pain of the natural world and my role in it.

Each of the traits in the web of disconnection is linked with all the others. In addition, they all feed into the cycle of continuation (comfort, security, and normalization), which keeps the dysfunctional process entrenched in my psyche. These psychological forms of suffering are then complexly linked with the other three quadrants in the integral matrix: my individual behaviors, our cultural adaptations, and our collective physical impacts.

Conclusions

If you made it this far, I want to extend my gratitude to you for taking the time and emotional energy necessary to engage with this topic. It’s not easy material. And, admittedly, I outlined the problem without making any attempt to offer solutions.17 But I will say that for myself, when I first developed the material in the Web of Disconnection, I felt an immense amount of relief. If properly understanding the problem is half of the solution, then we’ve taken some bold steps here today. In reframing my emotional disconnection from the metacrisis as an aspect of the metacrisis itself, I was able to ease some of my self-criticisms and reorganize around my internal states. It gave me a useful map to begin to start working on myself from a different angle: the more connected I am, the more the world heals.

Let’s return now to the question posed by the title of this article, how to feel about the metacrisis? My answer is that it doesn’t matter what you feel. But it does matter tremendously that you feel whatever is present for you on this topic. Feeling is itself the antidote. The opportunity that we now have is to step beyond the web of disconnection and into an embodied, emotional relationship with the state of the world. Viewed through this lens, developing our emotional capacity is among the most immediate, empowering, and important steps we can take.

I’ll leave you today with a quote from Roger Walsh, which I find to be very inspiring:

From this perspective our current crisis can be seen not as an unmitigated disaster but as an evolutionary challenge, not just as a pull to regression and extinction but as a push to new evolutionary heights. It can be seen as a call to each and every one of us, both individually and collectively, to become and contribute as much as we can. This perspective gives us both a vision of the future and a motive for working toward it.

—Roger Walsh18

My answer to this question is: Yes, and it looks like non-violent non-cooperation. The blueprints for this form of collective action have already been laid out by Gandhi, MLK, and others.

“To combat this intolerance, the world religions need to become ‘conveyor belts’ of transformation, by including a full spectrum of spiritual-intelligence Views of their own teaching, reaching from egocentric to ethnocentric to worldcentric to Kosmocentric (that is, by covering the entire spectrum of basic structures and each of their Views’ version of their particular religious beliefs). Until then, stuck at a spiritual intelligence of Mythic ethnocentric, most of the world’s religions preach love and compassion, while practicing intolerance and jihad.”

The Religion of Tomorrow, Wilber.

“Integral brings a powerful revitalization of spirituality. In sharp contrast to the three prior paradigms that populate most of Western culture today, integral posits that spiritual truth is real, it is directly accessible by each individual, and it is fundamentally interwoven into every aspect of existence. This is a massive leap and promises a much-needed Great Turning for Western civilization.

“Integral spirituality reaches down to include and synthesize spirituality from all prior paradigms. Because the integral paradigm is interested in supporting each paradigm that came before it, instead of fighting or destroying them, integral is uniquely available to receive each one’s gifts. Truths are discovered and celebrated within indigenous spiritualities, organized religions, science and philosophy, and New Age mysticism— literally every paradigm represented in our culture. Instead of asserting a single spiritual truth, at integral, I find common truths across traditions.”

The Organic Masculine, Sturm.

“In each instance of integral power, the focus has moved to empowerment. Organicity, kaizen, and semiotics each actualize individuals and collectives through their skillful use. The adage that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely is only true for first-tier types of power. Integral power is about harnessing and participating with the power of life. At integral, I’m more interested in becoming a conduit for power than holding power over someone else. Integral’s primary focus is on harnessing our self-arising natural power toward well-being and growth. External, proscriptive, and authoritative forms of power may still serve a developmentally appropriate purpose, but these are no longer the primary tools of the integral paradigm.”

Primal Drives, Sturm.

Adapted from Ken Wilber.

“The main point is that every holon has four dimensions of being-in-the-world. No quadrant is primary, first, or more fundamental than the other three. Therefore, we say holons tetra-enact across the four quadrants. A holon’s existence is mutually self-arising and self-constituting across the four quadrants. For instance, a tomato plant perceives sunlight (upper-left), manifests physically (upper-right), relates vegetatively (lower-left), and participates in an ecosystem (lower-right). This four-quadrant map provides a holistic address for every holon.”

Primal Drives, Sturm.

“My position is that every holon has (at least) these four aspects or four dimensions (or four “quadrants”) of its existence, and thus it can (and should) be studied in its intentional, behavioral, cultural, and social settings. No holon simply exists in one of the four quadrants; each holon has four quadrants.”

Sex, Ecology, Spirituality, Wilber.

Integral Ecology.

The Tao of Liberation.

Coming Back to Life.

The Body Keeps the Score, van der Kolk.

“Not all addictions are rooted in abuse or trauma, but I do believe they can all be traced to painful experience. A hurt is at the centre of all addictive behaviours. It is present in the gambler, the Internet addict, the compulsive shopper and the workaholic. The wound may not be as deep and the ache not as excruciating, and it may even be entirely hidden—but it’s there. As we’ll see, the effects of early stress or adverse experiences directly shape both the psychology and the neurobiology of addiction in the brain.”

In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts, Mate.

“Our inability to stop our suicidal and ecocidal behavior fits the clinical definition of addiction or compulsion: behavior that continues in spite of the individual knowing that it is destructive to self, family, work, and social relationships.”

“The Psychopathology of the Human-Nature Relationship,” Metzner in: Ecopsychology, Kanner.

“Technology, Trauma, and the Wild,” in Ecopsychology, Kanner.

Staying Alive: the Psychology of Human Survival.

“Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates,” World Health Organization.

In Primal Drives, I frame this discussion as a form of ecological violence and compare it with other collective forms of violence like oppression. I then offer a roadmap to address these forms of violence by moving collectively into nonviolence and sustainability. You can find my take on how to address these issues there.

Staying Alive: the Psychology of Human Survival.